Probably the most notable feature of the hippies was that almost all men had long hair. In fact, long hair was such a staple of hippie culture that the most iconic artistic portrayal of it—the musical turned motion picture Hair—was named after it. In the title song, the male leads sing together, “Flow it, show it, long as God can grow it—my haaaair!” Whenever I hear it, I still feel like loosening my nonexistent ponytail and letting my hippie hair fly in the breeze.

Why was long hair the emblem of the sixties’ counterculture? Put another way, why is it that in most conservative or traditional societies, men’s hair is typically short and trimmed? There are exceptions, of course, but generally, if you see a man with long hair, you can be fairly confident they lean liberal or progressive rather than conservative.

The obvious answer lies in cultural roots. The conservative world is grounded in the Enlightenment, which championed culture—from the verb to cultivate. The notion that human civilization is based on transcending nature is reflected in the belief that men, who embody the “masculine” idea of taming and controlling nature, should trim their hair. Since women are associated more with nature than culture, it is considered permissible and even desirable for them to grow their hair long. (The notion that women’s hair grows faster is a myth: the average growth rate for hair is the same for both genders.)

The liberal world, on the other hand, is rooted in Romanticism, which idolized Nature with a capital N—the wild, untamed state of things before civilization, which, according to this view, we’re ruining with our man-made culture and technology. From this perspective, one symbolic way of returning to primordial nature is for men, the agents of masculine culture, to grow their hair “long as God can grow it,” without interference.

But we want to dig deeper, and for that we’ll turn to the Jewish mystical wisdom of Kabbalah.

Hairy Thoughts

According to the Torah, man was created in the image of God. Kabbalah teaches that every physical organ has symbolic significance, reflecting a divine spiritual attribute. While many animals—including primates, our closest relatives—have fur all over their bodies, human hair grows primarily from the back of the head, with men also having facial hair.

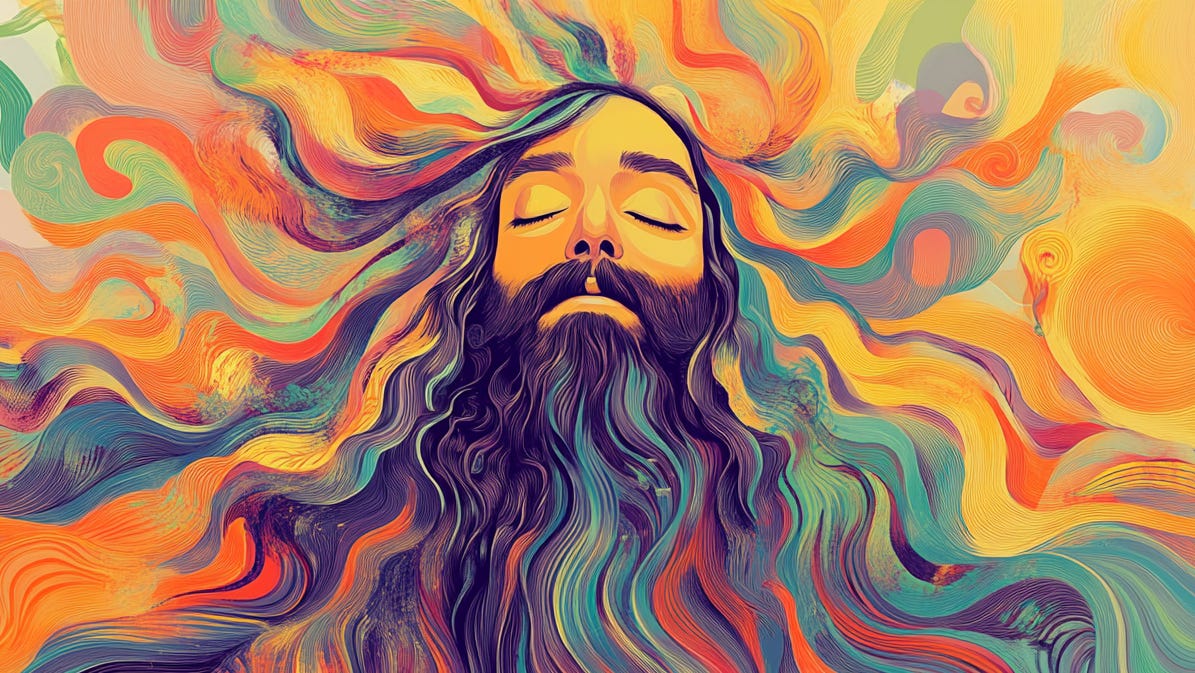

In Kabbalah’s view, this is no coincidence. Hair is intimately associated with… thoughts. Our hair is considered the external manifestation of the thoughts in our brain as they, so to speak, overflow and pour out of our heads. More specifically, hair embodies the thoughts that cannot be contained within the rational vessels of our intellect—our wild, unconscious thoughts that are harder to tame.

To the modern ear, this concept may sound, to say the least, unusual. It feels like something straight out of an esoteric, medieval treatise—because, in many ways, it is. But if you think about it, it’s also an oddly profound idea. Our heads are constantly overflowing with both unconscious thoughts and physical hair. It makes a quirky, associative kind of sense to see the latter as a manifestation of the former.

Interestingly, this notion is reflected in the Hebrew language, which, according to Judaism, is the language of creation. The Hebrew word for hair, se’arot (שְׂעָרוֹת), is cognate with, and stems from the same linguistic root as, one of the words for thoughts, hasha’rot (הַשְׁעָרוֹת), suggesting they mean similar things. (In a more tongue-in-cheek observation, another Hebrew word for thought, hirhur, sounds remarkably like the English word hair).

Why, then, does Judaism permit women growing their hair long, while men are instructed to trim theirs? The Kabbalistic and Chassidic answer is that women are more in tune with the subconscious. Their free-flowing thoughts are considered more naturally refined and don’t require cutting. In contrast, men’s subconscious thoughts are seen as rougher and more unruly, thus needing refinement through trimming.

That said, Judaism considers it more modest for women to tie up their hair. In fact, one Hebrew word for braiding hair, beniyah (בְּנִיָּה), is cognate with binah (בִּינָה), meaning feminine intelligence. These words are even strongly connected to the story of the creation of woman. When God created Eve, it is said that He “built” her (va-yiven) from Adam’s side. We often think of this side as a rib, with the “building” referring to constructing it into a fully grown woman. But a famous Rabbinic opinion states that Eve was fully formed from the start. So, what does the “building” mean? The answer is that God braided her hair.1 From this word va-yiven, “built,” we learn that women were endowed with binah, feminine intelligence. Binah is therefore about taking the free-flowing energy of the unconscious and, instead of cutting it, braiding it—tying it into beautiful forms and thereby elevating it.

Abraham and Sarah’s Hippie Commune

A beautiful Talmudic story touches on this theme.2 It is told that Rabbi Bena’ah (a name curiously similar to binah) once set out to map all the burial caves in the land of Israel and mark them for impurity, so priests could avoid walking over them. He eventually came to the Cave of Machpelah, the famous tomb of the patriarchs in Hebron, the resting place of, among others, Abraham and Sarah, the first Hebrew patriarch and matriarch. When he arrived, he saw their spirits, which still inhabit the place. And what were they doing? Abraham was resting his head in Sarah’s lap, and she was carefully combing through his hair, apparently searching for lice!

This surreal story contains profound wisdom. Abraham is depicted as a kind of proto-hippie, with long, flowing hair that, among other things, invites lice. (The Hair song even mentions making hair a “home for the fleas.”) This may sound anachronistic or even sacrilegious to some, but it aligns with Abraham’s character. He is considered the epitome of loving-kindness and peace. He famously opened his tent to all four sides to welcome guests, and sought to uncritically convert everyone to Judaism. He even loved his wayward son Ishmael, despite Ishmael’s attempts to harm Isaac.

The problem is that if these notions of peace, love, and unconditional acceptance are allowed to run wild, they invite trouble—external forces that infiltrate and, like leeches, seek to exploit their vitality. These are the “lice” infesting Abraham’s hair.

This is where Sarah steps in. Sarah is considered the greater prophetess of the two. When Abraham wanted to raise Isaac and Ishmael together, Sarah insisted it was wrong and that Ishmael and his mother, Hagar, should be sent away. God intervened, saying, “Everything that Sarah tells you—heed her voice.”3 Sarah recognized that, while the idea of universal coexistence is noble, it doesn’t always work in reality: Ishmael posed a danger, and Isaac needed protection. For both their sakes they needed to grow apart. And it wasn’t just Ishmael: Sarah regularly vetted the converts Abraham wanted, discerning who was genuine and who was not.

In the Talmudic story, Sarah continues this role. Abraham has utopian visions of universal love and world peace bursting from his head. At their core, these thoughts are holy and will be fully realized in messianic times, but their practical implementation is rife with dangers. Sarah combs through them, removing any misguided interpretations or applications that may distort them.

Giving the Inner Hippie a Haircut

Sarah represents the process of taking the lofty ideals of the liberal mindset—equity, social justice, gender equality, open borders, free welfare, and global peace—and grounding them in reality. These ideas are good at heart, but implementing them simplistically, without foresight or nuance, often leads to dire consequences which may even be the total opposite of the original vision. A famous case in point is of course Communism, which began as a utopian vision of equality but ended in dystopian dictatorships, with widespread poverty and oppression.

So, what can we do with the urge to grow our hair long, to “flow it, show it, long as God can grow it”? For women, it’s permitted because their innate realism is trusted. But what about men? Here, Kabbalah and Chassidut offer an intriguing proposition: channel that urge into facial hair rather than head hair. While head hair symbolizes unrectified, unconscious thoughts, the beard represents intentional, refined, conscious thoughts.

I’m not saying all men should grow beards (though I do think that would be cool). Rather, I’m saying that the hippie energy of loosening up, embracing nature, and loving every human being shouldn’t be totally dismissed—it just needs to be channeled properly.

Here’s to the holy hippies we’re meant to become!

This essay was translated through the kind help of my Patreon supporters:

Adam Derhy, Bruno Schall, Devori Nussbaum, Doctor Chike, Jason Kiner, Ricardo Moro Martin, Tamar Taback, Wealth Rabbi, Yacov Derhi, Abigail Hirsch, Aryeh Calvin, Asi Ressler, Bracha Meshchaninov, Bracha Schoonover, Brendon Lefton, Chana Milman, Charlotte Chana Coren, Cindy Abrams, Courtney LeDuc, Daniel Nuriyev, Deah Avichayil, Deena Feigin, Devorah Benchimol, Dina Ariel, Dvora Kravitz, Eduardo Gormedino, Eli V., Elisheva & Moshe Cerezo, Emanuel & Elisheva, Esther Brodt, Gavriel, Golan Friedman, Hilorie Baer, Hinda Helene Finn, Inbal Reichman Cohen, Jabula Su, Jeniffer Volz, Karin Wieland, Laurie Good, Leo, Malka Engel, Mariam Urban, Mark Lewis, Melanie Stokes, Meryl Goldstein, Michal Daneshrad, Michelle Houseden, Michelle Miller, Min Chaya Kim, Miri Sharf, Miriam Berezin, Nechama R., Randi Gerber, Raphael Poliak, Richard & Barbara Honda, Reuben Shaul, Rivka, Rivka Levron, Roswitha Forssell, Ruth Seliger, Sam, Shaindel Malka Leanse, Sheri Degani, Shlomo Shenassa, Shoshy Weiss, Sofia Henderson, Stacy Berman, Stacy Hatcher, Stuart Shwiff, Susan Hyde, Thatfijikidd, Tsvi Rosner, Victoria & Alon Karpman, Yael Eckstein, Yael Nehama Respes, Yaffa Margulies, Yoon Pender, Youry Borisenkov, Zeltia Lorse

Babylonian Talmud, Berachot 61a.

Babylonian Talmud Bava Batra 58a.

Genesis 21:12

Do these themes have any relation to Samson and Nazirites?